By Dr. Yohannes Mengistu

In my previous blog published a year ago on “The Impact of COVID-19 on Africa,” I tried to anticipate the impact the COVID-19 pandemic would have on Africa, including the obvious health care crisis and the direct or indirect effect on the economy, leading to an even greater economic plunge. Moreover, I speculated on what actions could be taken to tackle the transmission of the disease, to decrease the morbidity and mortality of the novel coronavirus.

On March 13, 2020, the first COVID-19 case was detected in Ethiopia. Officials stressed the commencing of COVID-19 infection prevention and control practice in a public announcement. The announcement was followed by social panic, which not only brought changes in the expected social status quo but also in subsequent scarcity of hand sanitizers, masks, and hygiene products. It also resulted in inflation on goods and services. The Ethiopian government, in the early days of the pandemic, then instituted numerous mechanisms to tackle the transmission of the disease and address the inflation. A state of emergency was declared and near-sufficiently adhered to by the public; it stayed in place for five months. In addition to these mechanisms and the heroic acts of health professionals throughout Ethiopia, the fewer numbers of international travelers and migration, along with limited urban to rural movement, thankfully contributed to a less-than-expected transmission of the virus, as well as mortality and morbidity.

However, the early stages of the pandemic control in Ethiopia, which was actually satisfactory, have led to social distrust of the government. Unfortunately, government representatives were less than cognizant of the cultural and social aspect of the issue, including low scientific knowledge in Africa in understanding the natural history, dynamics and concept of the disease, compounded by low health care-seeking behavior and generalized stigmatization of the ill. Public outcry about inflation of goods and food products on top of the daily-income-dependent living standard of the majority led to incautious ways of living as it was before COVID-19 or almost close to that.

These factors, in turn, have now led to what happens to be the “second wave” of the coronavirus pandemic in our country. Ethiopian Ministry of Health medical service directorate general Yakob Seman, MPH, updates figures daily. Currently, the positivity rate nationally is more than 25% and more than 20% in five regions of the country in consecutive weeks. These numbers indicate the need for lockdown measures to be taken under WHO guidelines. There is also a significant rise in daily ICU admission and deaths. Among few others, Yakob Seman has been urging the government and the public to institute stricter measures to tackle this deadly virus.

Ethiopia, a Sub-Saharan country with over 110 million people, conducted 2.3 million COVID-19 tests as of March 27, 2021, with daily test conduction below 10,000. With this positivity rate and daily sample collection, one can reasonably conclude that both the number of daily cases and deaths are underreported. This is by part attributed to long turnaround time (time from sample collection to result notification) because there are only 72 laboratories for COVID-19 sample analysis in the country. Adding to that are inadequately trained human resources (from sample collection to interpretation, transportation, and biomedical maintenance teams), lack of infrastructure, logistical constraints (shortage in test kits and consumables), lack of reference laboratories and such.

For example, at the hospital in which I work, patients who are highly suspected of having COVID-19 and who require administration of high flow oxygen or ICU care are regularly denied access due to delays in their results, pending a decision on where to admit them: COVID-19 treatment centers or regular hospitals. Unfortunately, COVID-19 isolation centers are not well equipped with ICU equipment and setups, and during this delay in diagnosis some patients die and are not reported as COVID-19 deaths.

As a member of the rapid response team for COVID-19 in our hospital, I can report that our team is faced with multiple challenges in handling both suspected and confirmed COVID-19 cases. In the previous couple of months, bed utilization has been to the fullest level and positive patients must wait for beds, including in the ICU, to be free in treatment centers. Adding to this, there also has been a critical shortage of oxygen after the main plant exploded in our capital city, where the majority of positive cases and ICU patients are present. This has had a significant negative impact on already overwhelmed health care facilities and patient outcomes. Additionally, this has created significant impact on health care professionals, creating burnout and dissatisfaction in their work that leads to psychological burden. Therefore, it is becoming evident that the anticipated impact of COVID-19 on Africa, about which I wrote in my previous blog, is happening currently.

Despite this, it is still possible to tackle the transmission of the virus and its negative impact on our communities. Serious measures, including suspending schools, restricting mass gatherings, mass sporting events, closing bars or limiting customer numbers, mandatory mask and sanitizer use in all public places, and early detection, isolation, and treatment must be taken seriously. Especially for Ethiopia, which is planning to hold the national election which was postponed last year due to COVID-19, bringing so many people together for an election is concerning, considering the current positivity rate and death numbers. Mitigation measures must be taken, and ideally commenced early.

Moreover, the international community and donor organizations are needed to help Africa in fighting this pandemic, as it cannot be done alone, but with joined hands. Specific areas of help that I believe currently are providing personal protective equipment for health professionals, providing mechanical ventilators for use in ICU settings, and enhancing the testing capacity of nations like Ethiopia. In addition to this, fair distribution of much needed vaccine for Sub-Saharan nations which cannot compete for the international vaccine demand should be addressed and the equitable distribution of vaccine should be ensured.

Ethiopia has so far reached a major milestone, receiving 2.2 million doses of the Astra Zeneca COVID-19 vaccine – but keep in mind our population is 110 million souls. Health care professionals and high-risk groups are receiving the first phase of the vaccine. Many public officials have received the vaccine in a public way in order to encourage people; I am one of those who got the first shot of the vaccine as a health professional.

No one is safe unless everyone is safe, says the World Health Organization and I agree with them on this important point. Equitability regarding vaccine distribution should be everyone’s responsibility while we implement and continue prevention protocols and treat those who are already ill. And finally, care and psychological support for health care professionals, who are the first line in fighting this virus, should be given great attention, now and in the future.

Update: Since this piece was submitted for publication, conditions in Ethiopia have thankfully begun to improve. Ethiopia’s health care workers continue to work hard to stem the tide of the pandemic and we all pray for continued progress.

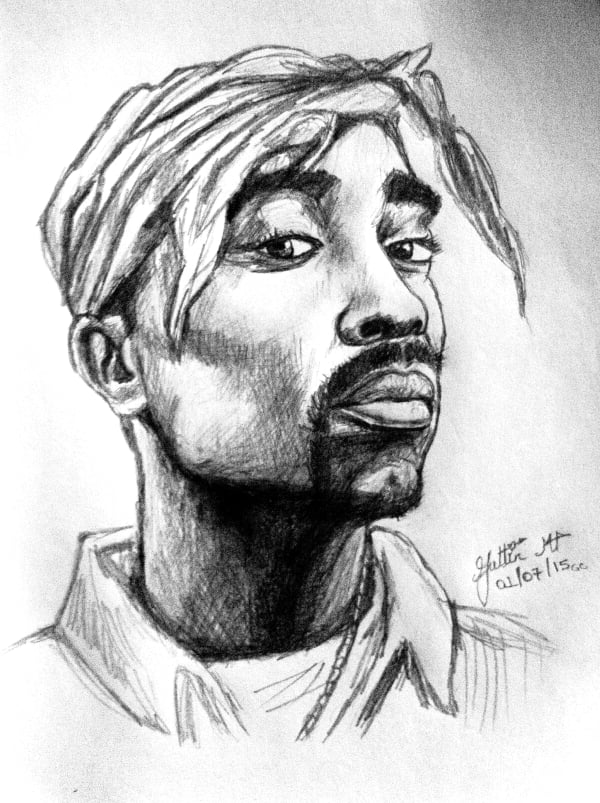

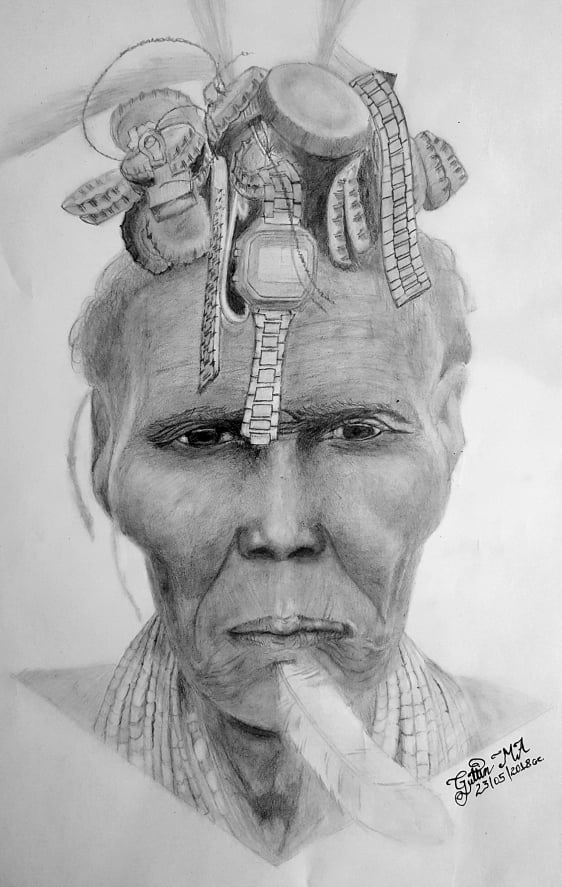

Dr. Yohannes Mengistu serves as a general practitioner, OR Department Director, Incident Officer and Risk Communicator in the COVID-19 task force at Menelik II Referral Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Dr. Mengistu draws to relax; all drawings featured in this blog are his original artwork. Dr. Mengistu’s work has previously appeared in Physician Family Magazine and the Physician Family Blog. You can contact him at guttinma@yahoo.com.